Written by Jon Boen and edited by Drew McManus; originally published at polyphonic.org.

It would be difficult to find a musician who hasn’t had this thought cross their mind at one point or another in their career, and Lyric Opera of Chicago Principal Horn, Jon Boen, is no exception. However, in Jon’s case he discovered that developing the initiative to capture artistic control is accompanied by a great deal of personal risk. Furthermore, the amount of that risk increases proportionately with the size of the project.

In this article, Jon recounts the details related to the costs, both economic and personal, of commissioning, performing, and recording a major concerto for French Horn and orchestra.

~ Drew McManus

Ever since I started playing the French Horn, I’ve always wondered about the origin of each new concerto that I’ve encountered. Was it written for a specific performer? Who premiered the piece? Did the composer have a personal relationship with the musician for whom it was written? What was the inspiration for the composer? Where was it first performed? Was it well received? Many questions such as these can be easily answered through historical research.

Ever since I started playing the French Horn, I’ve always wondered about the origin of each new concerto that I’ve encountered. Was it written for a specific performer? Who premiered the piece? Did the composer have a personal relationship with the musician for whom it was written? What was the inspiration for the composer? Where was it first performed? Was it well received? Many questions such as these can be easily answered through historical research.

However, I’ve still always marveled at what it might be like to be in the midst of bringing a new composition to life. I surmised that it must be extremely exciting to experience the process first hand. Eventually, I found myself wondering “How could I create a new concerto?” Well, obviously, I’d need a composer who was inclined to spend the time to write it, a commitment for performances, a lot of money, and time to practice. At that point in the process, the only thing I had from that list was time. As such, commissioning a horn concerto was more of a hopeful dream than a serious project.

Nevertheless, I remained committed to the idea, and by 1983 I had developed contacts that eventually resulted in securing the commission fee and funding for performances. By that same point in time I had also established myself as a professional player and developed a relationship with an excellent composer, so I brought all of these resources together to create what would become known as Horn Concerto.

Finding The Composer

I met Jan Bach in 1974 during my last year of high school while playing as a substitute musician with the Rockford Symphony Orchestra. The following year, as a freshman at Northern Illinois University, I joined the RSO horn section and commuted weekly to Rockford for services. Jan was serving as the Principal Horn of the section at that time and since we lived in the same area, we drove to services together.

We had great conversations during the car trips and consumed copious amounts of fresh cookies as we detoured past my parents’ home before heading back to NIU. I admired Jan on several levels: as a musician, a theory and composition professor, and especially as a gifted composer. Some of Jan’s works which I’ve also personally performed are his Laudes For Brass Quintet and Four 2-Bit Contraptions.

Furthermore, Jan was intimately familiar with the French Horn’s capabilities, was acquainted with my abilities as a horn player, and was (and still is) extremely well respected in the brass community. All of these things led me to feel that Jan was an ideal choice to write my horn concerto.

Developing The Ability & Commitment for Performances

Being surrounded by the world’s finest voices and playing solo horn in the Lyric Opera of Chicago provided me with a wonderful opportunity to develop as a performer.

While I was a senior at NIU, my teacher, Bill Klingelhoffer, left his position at the Lyric Opera of Chicago to join the Houston Symphony. Gail Williams replaced him at Northern for my final semester. Both Gail and I auditioned for and made the final round for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra horn section. In the end Gail moved over to Orchestra Hall with the CSO and one year later, I auditioned for and replaced her as Principal Horn of the Lyric. Consequently, being surrounded by the world’s finest voices and playing solo horn provided me with a wonderful opportunity to develop as a performer.As an outgrowth of the Lyric Opera musicians’ desire for a longer season, The Orchestra of Illinois was founded in 1979 as a co-operative orchestra governed by the musicians. For the inaugural season, Jan Bach was commissioned to write Gala Fanfare, which was well received by the audience and critics. Several years later, I knew that I wanted Jan to write a concerto for me, but I still needed the guarantee of at least one performance. I approached the Orchestra of Illinois’ Board of Directors with the idea, and they accepted my proposal. The premiere was planned for the spring of 1983, and my dream had moved from being an idea into becoming a full fledged project.

Securing The Funding

Everything at that point was falling into place with the exception of finding the funding to cover the commission fee. I agreed to cover half of the expense out of my own pocket, but we still needed to find a source for the remainder. Board member and Orchestra of Illinois Principal Bassoonist, James Berkenstock, was acquainted with a neighbor of his, Betty Butler, who had recently lost her dear friend Hal Skopin to a massive heart attack.

Betty was a patron of the arts and had expressed an interest to James in commemorating Hal’s life in a special way. Jim suggested dedicating a new composition to Hal, in particular, a horn concerto, and Betty enthusiastically embraced the idea. Finally, the final pieces of the puzzle fell into place and my dream was actually going to happen!

The Inaugural Performance

Jan wrote most of the concerto over the summer of 1982. The extraordinary love story of Betty and Hal and his passing contributed greatly to the composition’s structure which Jan illustrates in his program notes:

“The concerto was a joint commission by Mr. Boen and Betty Bootjer Butler, a citizen of Evanston and patron of the arts who wanted something special to commemorate the life of her dear friend, Hal Cyril Skopin, who died abruptly at age 65 during one of his early morning jogs. The work is in three movements. The first, Fantasia, is cast in standard sonata-allegro form and features off-stage horn calls and an extended cadenza for the soloist. It is a series of continually shifting musical images both familiar and disturbing. The second movement, Elegy e Scherzo, is the only movement with specific programmatic connotations. Cast in ternary form, its mournful outer sections recall features of the bel canto aria, a musical form central to the Lyric Opera’s repertoire. The contrasting middle section is a quickly moving orchestral “jog” interrupted abruptly by a recurrence of the movement’s opening: dark musical gestures representing death. The last movement is a jovial, fast-paced Rondo, sometimes utilizing Caribbean rhythms and percussion instruments (it was on a Caribbean holiday that Betty met Hal) and concluding with a “Jan” session in which all five hornists play polyphonically to the accompaniment of clapping from the other members of the orchestra. The Chicago Tribune’s music critic John von Rhein understood the intention of the work; and after the June, 1983, premiere, he wrote, ‘The circumstances might have produced an extended elegy, but that was not what Bach intended…the music dances with the joy of living.’”

The work was a real challenge and it took me approximately six months to learn the new concerto. I was now living the dream of bringing a new work to life that I had envisioned since the time I began playing the horn in the seventh grade and I was creating the performance tradition for this piece; in essence, it was mine to forge. Through many hours of practice, I mastered the multitudes of technical passages for this 40 minute composition, including valved quarter tone scales. The musical shapes emerged. Jan created a piano reduction of the score and, working with an accomplished pianist, helped outline the accompaniment. But hearing the orchestra live during the first rehearsal was more thrilling than I imagined!

The premiere was exciting, and the work was well received by listeners and critics alike. A total of three performances were given throughout June, 1983, including an appearance at Orchestra Hall in Chicago for the American Symphony Orchestra League convention. During that weekend, I was invited to perform the concerto the following year with the Lincoln Symphony (NE). Following that performance, the reviews were once again exalted. All of this activity led me to think that I was on my way to more engagements and, hopefully, a recording.

It just didn’t seem possible that this could be the finale to my dream. Fortunately, unbeknownst to me, things were about to change in 2001.

Unfortunately, the initial commission in 1983 did not allow provisions for a recording project, and as time went by, there were no more performances in sight. I was feeling regretful because here was a successful contemporary composition that had taken me a long time to prepare, yet no one seemed interested in programming it, let alone recording it for posterity.My mind filled with hindsight and doubt. Should I have been more assertive with the Orchestra of Illinois Board during the original planning sessions? Where would I find the time and money to organize a recording session? How could I get people interested in programming additional performances?

It just didn’t seem possible that this could be the finale to my dream; and for 17 years following the initial performances, this seemed like the reality I was destined to live. Fortunately, unbeknownst to me, things were about to change in 2001.

Little did I realize in 1983 that Betty Butler was not finished with her support of the project. One day, in late 2001, Jim Berkenstock informed me that Betty had passed away. Although she was a person of modest means, Betty had left money in her estate to Symphony II (now known as the Chicago Philharmonic). Her children were consulted concerning the use of use of the funds, and they suggested a revival of the Horn Concerto. It was decided that Betty’s posthumous gift would be the seed money for a performance of the Horn Concerto, which was eventually scheduled for May 30, 2004, with the orchestra. This would be my chance to record the concerto since the rehearsal expense would be part of the orchestra budget, not a cost of the recording itself. However, I still needed to prepare a realistic budget and somehow raise the funds.

The success of this venture would hinge on the resources of my professional and personal contacts, which, by necessity, would ultimately expand . By the end of the project, my contacts provided me with:

- Budget and Grant preparation

- Fundraising advice

- Photography

- Graphic design

- Production and Engineering

- CD pressing

- Booklet printing

Chicago Philharmonic had already established a relationship with the Aaron Copland Foundation for Music from a previous recording project. Completing the application brought the entire project into focus. The requirements to receive a grant included providing the following information:

- Proof of an existing 501c3 performing arts organization

- Income/Expense statements for 2 years, plus the projected statement for the following year

- Name of the record label

- Name of the distributor

- Estimated date of release

- Quantity of first pressing

- List of all works to be recorded, including composer, performers and duration of works

- Projected budget

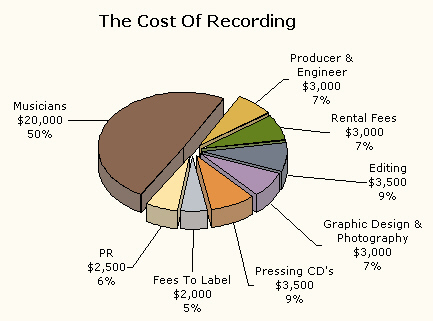

Chicago Philharmonic had previously worked with Equilibrium Records (an established label), Konrad Strauss (a producer), and Steven Lewis (an engineer) for a prior commercial recording. Chicago Philharmonic is a 501c3 organization. All contributions made on behalf of the project would be tax-deductible, which helped provide an incentive for donations. Examining budgets from comparable recording projects that Konrad had produced helped give me an idea of a realistic financial plan.

On advice from Equilibrium Records, the target length for the CD was approximately 75 minutes’ worth of music. The 40-minute Horn Concerto would be the focus of the recording, so we needed to choose an additional 35 minutes of music. The choices taken into consideration included:

- Historic links to the concerto

- Music featuring the horn

- Budget factors

Jan and I concluded that the remaining selections needed to be solo or small ensemble works in order to keep the costs down.

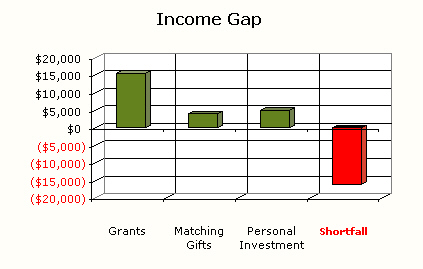

In June, 2002, Chicago Philharmonic received notification from the Copland Fund of a partial grant towards the Jan Bach recording project. Although significant, about $28,000 was still needed for completion. January 2003 arrived without any additional funding progress. Motivated by the reality that this project might fail, I became more proactive with raising money. This involved a higher level of risk, both financially and personally, as I stepped out on my own to seek contributions.

I realized that I had a resource which I had not previously considered. Sylvie Sadarnac-Studney, who runs her own public relations firm, is an avid arts supporter whom I met through my daughter’s first-grade class several years ago.

Sylvie helped me to compose letters and assemble lists of potential donors, as well as coaching me how to approach them in an appropriate manner. She also arranged for exposure in the local newspapers. Sylvie’s input really gave me a sense of direction and allowed me to begin securing contributions.

As I approached people for money, I discovered that the Copland Grant gave the project a great deal of credibility. On the advice from Sylvie, I made an appointment with Don Casey, Dean of DePaul University’s School of Music, where I’d been on the faculty for many years. Don is very involved in raising funds for the school and said, “The first dollars are the hardest to get.” He then committed to a significant pledge. I was on my way.

With the grant and the pledge from Dean Casey, the momentum continued with responses from some of the letters that Sylvie had helped me to write and from several Board Members from Chicago Philharmonic. We had raised enough money to cover the recording session orchestra payroll, but still needed approximately $16,000.00 to cover the remaining expenses.

My wife, Laura, suggested that we host a private soiree at our home with the intention of asking our contacts and potential donors, largely people from our neighborhood community, to consider becoming involved. She is a professional violinist who is always eager to have a party. It was the perfect combination—food and music! We sent out invitations entitled “Bach, Boen, and Brahms” and hosted a group of 45 in our home in mid-April—six weeks before the concert and recording session. We hired a caterer to ensure that our focus for the evening would be fundraising and performing, not playing the role of perfect host and hostess.

We began by performing the Brahms Horn Trio with our talented friend, pianist Melody Lord, in our living room, and we concluded with a commentary by Jan Bach which included the fascinating process of composing Horn Concerto. I played sections of the concerto with piano accompaniment provided by my former student, Tim Lenihan, and part of the French Suite for solo horn.

The response was wonderful. Most people had been to concerts before, but the home setting, appetizers, and conversation with the composer was a unique experience. No tickets were sold, and all contributions were entirely voluntary. Several sponsors had matching employee programs. The risk of absorbing the catering cost paid off as we made about $4,500.00 that evening. Later, a few more contributions materialized to get us within $8,000.00 of our goal. The remaining expenses that needed to be covered were:

- Editing

- Mastering

- CD insert

- Cover art

- Initial pressing fees

Preparing To Record

I had become very focused on fundraising, but still was keenly aware of the need to practice. Aside from being a very technically demanding work, at forty minutes, it requires extreme endurance. Through many years of Wagner operas, I’d learned that stamina is achieved through long hours of practice—no short cuts. I began practicing in earnest after the holidays and didn’t let up until after the recording session. My daughter, Olivia, can attest to this fact because she is still able to sing several different passages from the concerto to this day.

When it came time rehearse with the orchestra at the end of May, I was prepared. But the orchestra was practically sight reading because the music was not available until one day prior to the first rehearsal. Unbeknownst to me, a misunderstanding regarding the rental fees and recording rights developed between the publisher and Chicago Philharmonic. This was eventually resolved, but only in time to leave left four days for the orchestra members to learn their parts. Composers who would like to maintain more control with their works might want to consider the self-publishing options that are available today.

This difficult, unknown contemporary concerto would have to be perfected in a short amount of time. The horn section met separately to rehearse the antiphonal calls and the concluding “Jan” session when all four horn players join the soloist in front of the stage and volley jazz figures back and forth. Although conductor Larry Rachleff was very adept at shaping the accompaniment, tensions were mounting with everyone involved as the first complete run through would take place at the concert. Once again, my wife Laura had a great idea that involves music and food—throw a party for the orchestra after the concert. Everyone likes to be appreciated for their efforts and musicians are no exception.

We decided to provide a post-concert champagne reception backstage that included fantastic cakes from a premier bakery located in Chicago for the performers as a “thank you” for all of the extra practicing and their exemplary playing in pulling off this concert. We could see the smiles before the concert as the musicians walked by the large cakes and buckets of champagne on ice being set up backstage. The live performance was terrific!

Recording the Piece

A three-hour recording session with the orchestra was scheduled two days after the concert; but with breaks, the actual recording time amounted to only 2 ½ hours. Although the concert had been recorded, the producer had decided that hall ambience and audience noise precluded us from using any of the live material for the CD. We needed to cover 43 minutes of music in this recording session, so the pacing would be extremely important. Larry, Konrad, and Jan kept the session moving along, and managed to make sure that the Gala Fanfare wasn’t neglected.

Larry’s extraordinary rehearsal technique infused with humor kept a potentially tense atmosphere manageable, beginning with the time consuming events of latearrivals, numerous ensemble issues that needed to be addressed due to the limited amount of preparation time, late music availability before the concert, and even a problematic page turn. Eventually, all sections of the Gala Fanfare and Horn Concerto were successfully recorded during those 2 ½ hours. The orchestra feasted on leftover cake (no champagne!) and I continued the recording session alone for another 20 minutes by playing the cadenzas from the first and final movement, and took another shot at the treacherous multiphonic final note of the second movement.

With the major part of the recording and fundraising behind me, I could focus on the remainder of the project. Jan’s Helix, Four 2-Bit Contraptions and French Suite still needed to be recorded. I also needed a 16-page CD insert and a disk manufacturing and packaging company, and I needed to raise more money. My friend and colleague, Steve Lewis, was able to secure excellent donated spaces to record the final selections. It took me approximately six months to coordinate players, engineers, space availability, and rehearsals to complete the recording.

I would not have had the direction and focus without the incredible support and advice about marketing and production from my boss and friend, Jim Palermo, Artistic and General Director of the Grant Park Music Festival. Additionally, several key contacts came forward to help finalize the CD with gifts in kind.

I did not recall, but was reminded that on the evening of our soiree, that a close friend of Olivia’s violin teacher who owned his own CD manufacturing business had volunteered to press the discs and print the booklets at cost. I was elated by this generous offer.

Also present at our party in April were family friends Pam and Benny Kende who provided photography and graphic layout at a very reasonable cost. My fundraising needs had decreased through their generosity to the point that I was able to absorb the final expenses, including donating my solo fee back to the orchestra—a small price for the realization of my dream of bringing a new concerto to life and recording it for posterity.

Conclusions

In the end, this experience has helped me to understand the complexities involved with creating a major composition along with producing a professional recording. The process has also demonstrated the importance of reaching out beyond the comfort zone of professional musicians in order to generate active interest and support in the creative side of individual professional musicians.

It is hard to image that Betty Butler would have found a suitable artistic outlet if the series of events which brought her in contact with this project had not taken place. I hope that the Horn Concerto will become well known as it deserves a place in the solo horn literature. I will continue to pursue opportunities for further performances by sending copies of the CD to critics, conductors, artistic administrators, and colleagues.

I also hope that the example of personally becoming involved in a project like this will help to encourage other people in the arts to accept the inherent risks involved with following their own dream of producing a CD, concert, or video. I personally believe that classical music is alive and well and that we will be inspired to continue pushing forward in our endeavors.